TO THE EDGE AND BEYOND

- Art Refuge

- Sep 20, 2025

- 3 min read

September 2025

We are honoured to once again share this reflection from Alex Holmes, long-term volunteer in Calais, this time from his recent visit in September. All names have been changed.

‘TO THE EDGE AND BEYOND’

Watergang du Nord, Calais. The narrow stream that flows along the northern edge of the Courgain Est playing fields. Willow scrub on its southerly bank once sheltered many dozens of Eritreans’ tents. All that remains now is a broad carpet of wood shavings. Another campsite obliterated. The new site is an old site from which the Eritrean community was last evicted in 2022. Back then, it had become a swampland of puddle and mud.

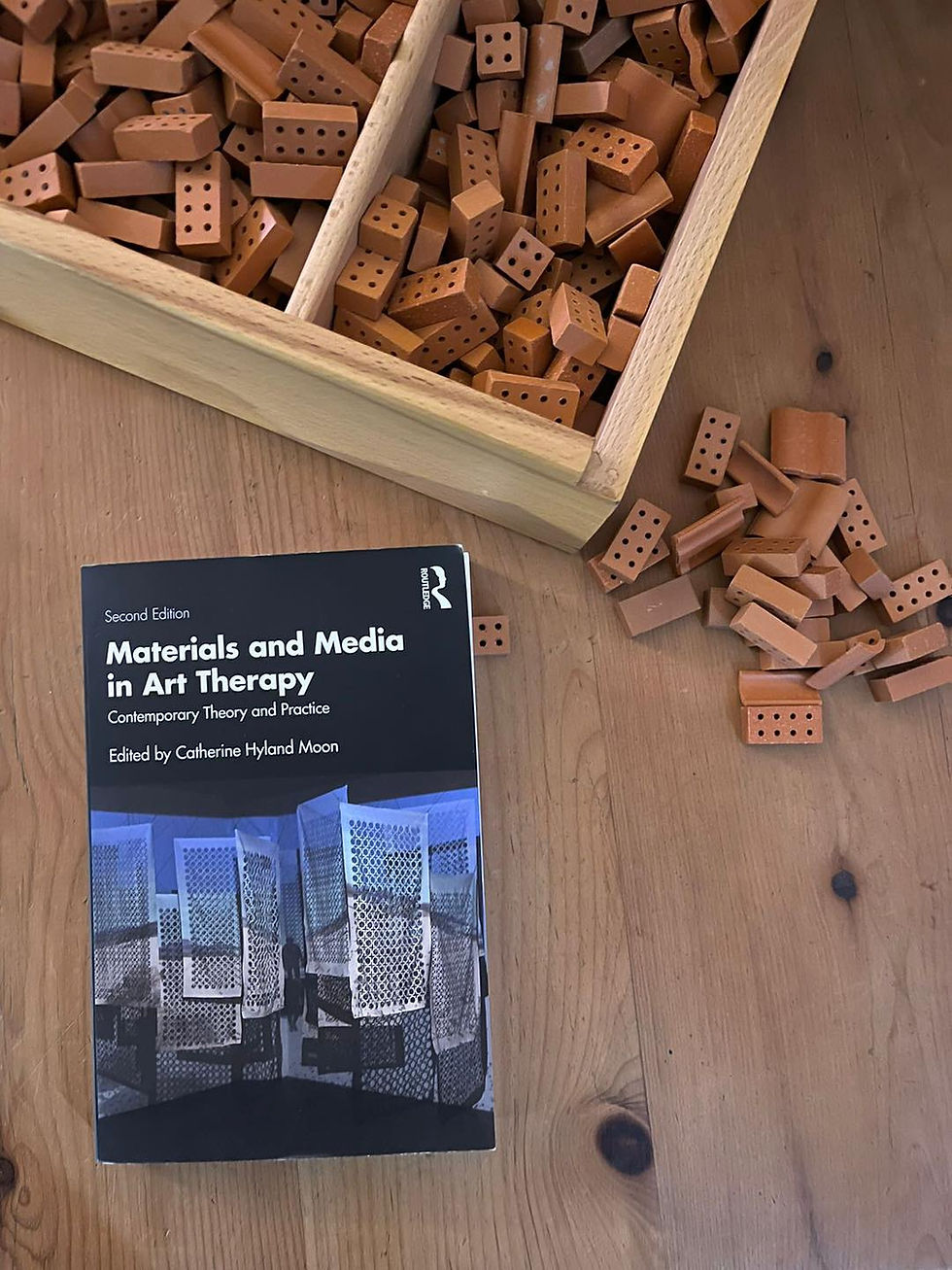

September. The weeks of summer dry have ended; torrential cloudbursts now herald the change of season. After a night of heavy rain, the fence is a festoon of wet clothes and bedding. Five sodden blankets topped by a sheet of plastic will serve as a soft underlay for Zehra’s tent. The sun emerges and there’s now a holiday feel. The grass, newly mown, is a sward of alternating dark and light green stripes. A pot of food bubbles on a fire. There’s music, Massawa delicately plucking the strings of a krar, a traditional Eritrean instrument. Finishing his tune, he passes the krar to Fikru who plucks and sings. Elsewhere, a game of dominoes is underway. Dawit is deep into a book. You want morning coffee? Hayat proffers a small paper cup emblazoned with the words ‘Café Royal, Switzerland’. The coffee is intensely sweet.

How is UK? Fireside, it’s the question asked again and again. This time it’s Ariam who’s asking. And then, Ariam, you tell your story. How you escaped from Eritrea to Israel only to be deported after five years to Rwanda and then pushed by the Rwandan authorities into Uganda. How you journeyed to Egypt, married and became the father of three children. Your dream is to reach the UK and have your family join you. But today is the very day that the UK government has added to its ‘one-in-one-out’ flagship deterrence deal with France by putting a halt to refugee family reunion.

A sudden electrical charge pulses through the campsite; everyone is immediately on edge. Robel and Hamid stride towards the gate at the field entrance to check who might be approaching. After a recent night attack, two Eritreans keep guard throughout the hours of dark. Yusef describes how his fingers were slashed and needed stitches. Now, Yusef, you sit on the edge of your seat clutching your bandaged hand, your eyes following Robel and Hamid. This time the approaching group are new arrivals, an Eritrean family with two children. The relief is palpable; the electrical charge dissipates.

But the police clearance that occurs every second day is expected and the camp must be dismantled. Anything left will be taken away. Within minutes it becomes a ghost site, emptied of people and possessions. There remains just a residue of occupation: Yohannes' wheelchair, a single trainer, a pair of trousers on the perimeter fence sporting the words ‘The Past’. And close to the edge of the smouldering fire, the abandoned krar. It will be dusk before anyone will dare return.

Wissant, a village at the Channel’s edge, down the coast from Calais. Another story told. Your story, Abbas. ‘Fishermen rescued you on your way from Libya to Italy, where you were the only survivor of a shipwreck involving 58 people*. In 2012, you were one of the first to testify that the Mediterranean border is killing people, but the UNHCR blocked the broadcasting of your testimony. You spoke of your route, Sudan, Lalibela and the restaurants in Addis Ababa. About the war when you were a child and how you left Assab by stepping over dead bodies. Eventually you were resettled in France where the psychiatrists wanted to pump you full of drugs. Rightly, you didn't want to take them. What's the point of taking medication in order to conform to a society that excludes us, destroys us, imprisons us in individualism? You have shown us once again, and once too often, how the border kills and how important it is to fight for freedom of movement.’ Words of tribute spoken at your graveside, Abbas. A single candle flickers in a glass jar. Hands are placed on your coffin. Gently you are lowered over the edge and into the dark earth.

شيخ روحاني

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني لجلب الحبيب

الشيخ الروحاني

الشيخ الروحاني

شيخ روحاني سعودي

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني مضمون

Berlinintim

Berlin Intim

جلب الحبيب

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://hurenberlin.com/

youtube

This reflection was powerful and deeply moving, capturing both the resilience and the pain of those living on the edge. The way it describes the stories of survival makes you pause and think about freedom and dignity in a whole new light. It reminded me of how strong statements—whether through lived experiences or even something as bold as a McLaren F1 bomber jacket become symbols of endurance and identity. Thank you for sharing such an important piece.